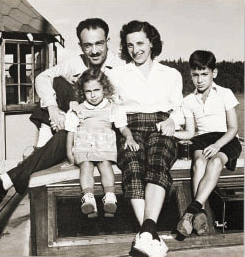

Kawagama, 1953:

First row, second from left, Beth Wolinsky;

Second row, from left: Nancy Shore, Susan Palter, Geraldine Sherman and, far right, Ruth-Ellen Soles

From the street, Holy Blossom Temple was glowing under late-December sunshine, an unlikely day for a funeral. My plan was to slip in, sit unobtrusively in the back row and say my private goodbyes to Elsie Palter. It had been almost 45 years since we'd spoken, but when I read the death notice in the Globe—"PALTER, Elsie Kaplan, Ph.D. (Psychologist and Camp Director). In her 91st year on December 15, 2000, at North York General Hospital"—I knew I had to attend.

As it turned out, I wasn't alone. The first voice I heard when I walked through the double doors was familiar. "This row is for our cabin," she said. It was Ruth-Ellen Soles, one of the Camp Kawagama girls. She was reconstituting our cabin as it had been decades before. I walked to the front and made my way slowly across the seats, hugging five cabin mates in turn, each one astonished to see the others there. Our lives touch only now and then, but we had been drawn to Elsie's funeral like swallows to Capistrano. For two decades, she and her late husband, David Palter, owned and ran Camp Kawagama in Haliburton. For many of those summers, we were among their campers, the girls of Cabin 22.

When I looked around, I noticed that other Kawagamites were present, recognizable despite wrinkles and paunches. But unlike our almost intact cabin, they sat separately. Perhaps we came together because our group had included Susan Palter, the owners' daughter, which made us vaguely special and held us more tightly in Elsie's sights.

In her eulogy, Susan talked about the many sides of her mother: her sewing, her flower arranging, her baking and canoeing, and her skill at knowing what children—Elsie never called us kids—needed. But the voice of Elsie rang most clearly when her grandson, Gilbert Palter, spoke. He told us that well into old age Elsie had kept index cards with psychological assessments of every Kawagama camper. Whenever one of us achieved some degree of fame, Elsie would peer over her newspaper and say, "I knew John would succeed. He was always a special child: intellectually developed beyond his years but also able to relate well to his peers." After reading about a former camper sent to jail, she remarked, "I knew that one would wind up in trouble. He was shifty-eyed and deceitful." When she compared her off-the-cuff comments with her original opinions inscribed on index cards, she was inevitably right. It's a further testament to her wisdom that those cards appear to have vanished.

Elsie may have been an uncommon camp director, but Kawagama shared much with other Ontario camps: Arowhon, Onondaga, YMCAPineCrest, Winnebagoe, the Taylor Statten camps. Across the Precambrian Shield—dotted with lakes and islands—city kids lived for weeks or months, learning things parents think are good for them: swimming, canoeing, a smattering of the arts. It's supposed to be fun, even character building, and for many it is. For some, it's boring or even traumatic. Either way, it's an accepted backdrop to the drama of our growing up, birchbark and rusty bunks the decor of our youth and symbols of Ontario's northern patrimony.

At Holy Blossom that day, the presence of the girls from Cabin 22, all of us about to turn 60, confirmed the atavistic value we place on camp. There we were, shoulder to shoulder, wanting to be counted as members of Elsie's community and to tell her surviving children what we probably should have told their mother long ago: Elsie Palter changed our lives. When Susan, walking behind her mother's casket, came alongside our row, she looked up and whispered loudly, "There you are!" Ruth-Ellen responded, "Yes, here we are." Then she turned to me and said, "There goes my childhood."

Kawagama opened in 1945, an optimistic year. On August 14, the older sister of one of our gang scrawled her name, the date and "VJ Day" on a rafter in her cabin. It stayed there throughout the 20 years the Palters ran the camp. Their success in this risky business was not a sure thing. Elsie Kaplan, the daughter of Russian immigrants, a tawny beauty with a military spine who played killer tennis, was one of the first women to receive a doctorate in psychology at the University of Toronto. Dave, a U of T engineering graduate who had gone reluctantly into his family's hat business during the Depression, was 36 and growing restless. They had two kids, Harry and Susan, and hoped that owning a camp might be the solution. Why not? Elsie had been girls' head counsellor at Arowhon, and Dave had gone to Camp B'nai Brith.

One summer day, paddling out from Russell Landing near Dorset on what was then called Hollow Lake, Dave rounded a bend and came upon Mountain Trout House. It was a fishing and hunting lodge with a main building and some outlying cabins scattered across a rugged island. "My parents took a flying leap and bought the place," says Susan. Before the first summer, Dave added more cabins, the main dock, and the Hub, the camp's cultural centre. Elsie discovered Hollow Lake's more melodic Indian name, Kawagama, Water-Between-the-Hills; choosing it created an instant connection to native mystique. The meeting circle behind the Hub was called Indian Council, and, like so many camps of the time, it promoted a version of native culture based on beaded headbands, war paint and canoes.

The Palters recruited their first campers from among friends and relatives, promoting Kawagama as a progressive Reform Jewish camp with Friday-night dinners of challah and chicken followed by camper-led services under a canopy of stars. In the first season, 125 came. "There was something special about that first year," Elsie told an interviewer much later, "a group of parents willing to send us their children. They were saying, ‘We trust you.'" About half a dozen of the core group of Cabin 22 came in 1945 as four-year-olds, playmates for Susan. Dave's young cousin, Joan Kagan, was one of them. The little ones were too young to read, she recalls, "so there were symbols where our soap and towels were supposed to go." Nancy Shore was another. Her parents were neighbours of the Palters in Lawrence Park. When she thinks about being sent to camp for two months at age four, she half-jokingly says, "My mother should have been charged by the Children's Aid." Another of the baby campers, Beth Wolinsky, happily left her bickering parents for the security of a surrogate family. "My home situation was such a stressful one, when I went to camp I was suddenly absorbed into something totally different." These girls came together for a dozen summers, occasionally accepting newcomers, like Ruth-Ellen and me.

By design, there were never more than 200 campers a season, which still generated plenty of personal histories to be stored in card files and Elsie's capacious brain. Near the end of her life, when asked what she wanted these children to achieve, she snapped: "In two words, their utmost potential. Pleasure. Love of outdoors. Skills that would contribute to their self-esteem. And friendship—I should have put that first."

Friendships in Cabin 22 revolved around Susan. One girl was ecstatic when she was invited to watch Elsie braid Susan's glossy brown hair in the Palters' cabin behind the dining hall. In time, deference would give way to defiance, Elsie and Dave's place offering an occasion of sin. "Susan and I had the nerve to go to her mother's cabin and smoke cigarettes in her bathroom, almost waiting to get caught," Nancy remembers. "Why did we do it there?" Perhaps to let the summer parents know their children were growing up.

When Susan graduated to stealing her dad's smokes, an elect group would crowd into the outhouse closest to the Palters' cabin. There, in a pre-marijuana circle, we would pass a Black Cat like a reefer, inhaling and choking, giggling madly. I didn't smoke in those days; so, brimming with virtue, I played the role of Group Flicker, knocking the ash off with all the savoir faire I could manage, working on my personal legend.

The girls of Cabin 22 twitched with anticipation before each season. Ruth-Ellen started counting the days after her birthday in April, "dreaming and wishing and wanting the time to go faster." The most eager campers were those who most hated school. Joan Kagan was already tall and angular, tough in an era when cute and cuddly were at a premium. Still, she remembers holding her breath "from the end of one summer to the beginning of the next." Susan Morgan, a chunky, bespectacled 14-year-old, was wretchedly unhappy at Forest Hill Collegiate, where she says being smart was OK but not as important as good hair and cashmere sweaters. She found salvation at Kawagama. At times, she felt the 10 months at home were just a waiting period before the two months of camp. "Without them, I would have spent the year with nothing to look forward to."

In late spring, our parents received the camp's clothing list: 14 pairs of underpants (laundry took a week), sweaters and jackets, shorts and jeans, insect repellent, flashlight, stationery for mandatory letters home, towels, a ground sheet and blanket pins for overnight bedrolls. Everything had to be labelled, to create the illusion that personal property would return with its owner. Helping my mother and grandmother sew tiny cloth labels on all my clothes, my name in bright red letters, was as close as I ever came to a quilting bee. About 10 days before camp, we stuffed everything into duffel bags, attached cardboard labels with the camp's address and shipped the bundles ahead.

The Monday after school ended, I boarded the early-evening train in Chatham, my hometown, joining campers en route from Windsor. At Union Station in Toronto, we hooked up with the kids from Buffalo before heading north. No one slept much; there was catching up to do. The counsellors passed the time deciding who was sexy and who wasn't, and calculating how much money the Palters made by charging each camper $450 a season and only paying the junior staff $25. Off the train at Bracebridge and onto buses for the hair-raising 90-minute ride over dirt roads, belting out camp classics, "Land of the Silver Birch" and "John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt." On the dock at Russell Landing, we waited impatiently for a boat that would take us to our island, 20 minutes—an eternity—away. Would we get The Trillium, named in one of Elsie's more poetic moments, with side benches that seated 30, or the larger Kawagama, Dave's beloved mahogany launch, which carried 40. "You couldn't just dash over," remembers Beth. "You waited and you waited, and the boat came, and at last it was your turn."

After landing, we raced to our cabin to jockey for the best bunk. When we were young, it was the one closest to the counsellors; later, the bed closest to Susan's. We jammed our clothes into rough wooden cubbyholes along the far wall and flung them on nails beside our beds. On slats above our pillows, we laid out our supplies of Nivea, calamine lotion and plastic hairbands. As much as we looked forward to our first night, settling in wasn't easy for everyone. "I always put my head under the covers and cried," Ruth-Ellen says. "I did until I was 18. It became a ritual."

Pangs of loneliness passed quickly. Ruth-Ellen had two older brothers at home; at camp, she had eight or 10 sisters. "We slept together. We ate together. We were together all the time." After lights out, we held Truth Telling sessions and indulged in an endless conversation. "What did we talk about?" Susan Palter asks now. "And laugh about, for so many nights?" It didn't matter much, because soon we'd drift off to sleep side by side, as though in one large bed, breathing in unison.

At seven a.m., a boy camper blew reveille on a bugle. We staggered from our beds, just made it to the outhouse, then returned to wash and brush our teeth over our cabin's single sink. A second bugle blast sent us running to the flagpole, where we stood at attention as the Canadian Ensign ascended. Then we crowded into the dining hall, the largest building on the island, for breakfast: eggs, pancakes or French toast, always cereal, and soft white bread slathered with peanut butter and jam. We ate with our cabin mates and then huddled together over the activities sheet, where we collectively decided on the day's program: instruction in a competitive sport such as basketball or tennis; quasi-military activities like archery and riflery; arts and crafts, horseback riding, sailing. "The culture of camp," says Susan Morgan, "was based on being in a cabin," the same cabin summer after summer—that was crucial. "You weren't a bunch of individuals; you really were this cabin group."

Kids who couldn't survive the pressure were skewered during brutal nights of Truth Telling. From the earliest years, one girl was punished for being "difficult" and "different," yet she kept returning for an annual trouncing. (As an adult, she chucked Judaism and Canada, joined the Baha'i and works at their headquarters in Haifa.) Successful campers quickly learned to make themselves indispensable, creating a unique role in the ongoing cabin drama, even if we didn't understand until years later what that role was. Nancy was the Good Friend, easygoing and confident despite her thick, almond-shaped eyeglasses. Ruth-Ellen, a perky kid with unruly cropped hair, wasn't particularly athletic but threw herself into everything with frantic enthusiasm. "I have this vision of me—skinny little me—flying around that camp." She became our Cheerleader, determined to boost team spirit. "Maybe that was part of my personality, to pick people up when they were down." After "terrible years of feeling too big," Joan discovered a talent. She could play the piano by ear. "That was a huge thing for me and put me in a whole other category." Susan Morgan joined Kawagama after an unpleasant stint at Winnebagoe. "I'd spoken to one Kawagama girl before camp, and she'd scared the shit out of me—there are all these ‘in' things and ‘out' things, and the chance of me getting into any of the ‘in' things was really remote." Much to her delight, she discovered that in Cabin 22 it was OK to be "brainy, quick and mighty edgy," a role she proudly assumed for four years.

If you lived in a small town, as I did, or went to a mostly gentile school, as Nancy did, camp was a way to meet other Jewish kids. From the time I was eight, I was bundled off to various Jewish camps, without much luck. When I arrived at Kawagama, a chubby, insecure 12-year-old, I decided that this summer, too, was going to be a disaster, that my life was more or less ruined. Until one rainy afternoon, first by accident and then quite deliberately, I made the other girls laugh. I was half possessed, standing in the aisle between two rows of roaring cabin mates, doing stand-up. It was my defining camp moment. From then on, I played Sharp-Tongued Wag.

For Cabin 22, 1955 was the magic summer. That was the year we turned 14. We no longer craved the attention of the most popular girls; we wanted the affections of the best boys. "In adolescence, a big part of the camp experience was having a boyfriend," says Beth, "and I didn't have one, ever." And without a boyfriend, we were miserable. At our camp, the best boys and most fashionable girls came from Buffalo, which existed in Ontario mythology as a stylish mecca for shopping and Sunday drinking. Kids from Buffalo set the sartorial standard. One year, they came with white wool Adler socks, madras plaid Bermuda shorts and little white dickies. The following year, it was no socks, khaki cut-offs and neckerchiefs. It was hard to keep up. "You'd think you had it right," Susan Morgan laughs. "Then you'd get to camp, and those Buffalo kids had stuff you'd never seen!"

Elsie, who once acknowledged that "primping and fancy hairdos were as much a part of national culture as baseball," encouraged relations between boys and girls in groups—though never in pairs. The carefully supervised dance floor provided the ideal meeting ground. But for many of us, Saturday-night dances at the Hub were torture. We wore dresses, propped up the walls and longed for romance while listening to "Mr. Sandman" and "Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing." When the evening ended, we crept back to our cabin, eyes down, trying to avoid couples groping beside the path or necking on the basketball court. Staff roamed the woods with flashlights searching for the disobedient.

For a time, I dated Nancy's brother, Milton. With three other couples, we formed the Teeter-Totter Gang, and practiced endurance kissing stretched out on motionless play equipment to see which couple could smooch the longest before coming up for air. Milton and I had the briefest of summer romances.

Lights-out Truth Telling turned into the Sexual IQ Test. "You wanted to score high enough to show that you'd had some experience," Susan Palter remembers, "but not so much that you were a slut. Have you ever been kissed? Have you ever been kissed on the lips? Have you had a butterfly kiss? A French kiss? Have you ever petted above the waist? Below the waist? And there were all these taboos, things you were supposed to have done and not done—an elaborate dance that could only have happened in the '50s. It was so pure." Five years after our adolescence ended, birth control pills arrived and camp sex changed forever. Susan Morgan thinks what we had was "wonderful, in a modest way." She would! In her first year, she landed Sharkey, one of the neatest Buffalo guys.

Weeknights, we held debates and performed plays on the Hub stage. When we weren't competing for boys, we were vying for parts. "Everything I know about Broadway musicals and Gilbert and Sullivan is rooted in that experience," says Susan Morgan. Although she was only a member of the backstage crew for the 1955 production of Trial by Jury, she remembers every line. So do I. Recently, watching filmed scenes from that production, I could hardly believe that failing to win a big part in something so awful broke my heart, but it did. After I blew my audition for Bridesmaid and was consigned to Chorus, I sat for ages at the edge of a cliff, contemplating a final, dramatic leap.

Once each summer, we dressed in white and waited near the dock for a brief visit from our parents. Apparently not trusting camp food, they brought coolers stuffed with pickled meats and dark breads. Seeing them was a mixed blessing: for some, it was a welcome break in the routine; for others, a painful reminder of the life that awaited them at home. Most of us came from standard-issue 1950s families—problems, sure, but a solid exterior. Beth was different. By 1955, her father and mother were separated, so while most of us stood hungrily on the dock, Beth was spinning an impossible fantasy. She knew her father wasn't living at home, but for that one day her parents reunited. When she saw them get off the boat, she couldn't keep from thinking, "Maybe they're back together!" They'd sit down like everyone else, Mom, Dad, three kids, munching pastrami sandwiches, and Beth would wait for the happy news that never came. When all the parents left, we joined in collective weeping, not to be consoled until that night in the Hub, when Dave showed his favourite movies, the Three Stooges or Laurel and Hardy. Kawagamites laughed, and things returned to normal.

In the waning days of August, the whole camp was divided into four teams (Red, Blue, Brown and Grey) for Colour War, a three-day Olympiad that rewarded both prowess and wit. We competed in marathon races, sailing contests, scavenger hunts and songwriting, vaguely emulating the games in ancient Athens. Four senior girls and four senior boys were elected captains by a secret ballot open to all campers and staff. In her final year, Susan Morgan was a winner and led the Brown Bagels—"rolling on to victory." She describes it as "the ultimate affirming experience," even though she's philosophically opposed to competition. "I'm sure people who get elected to Parliament don't feel better than I felt when I was elected Colour War captain."

More gruelling even than Colour War was our annual canoe trip—pitting Girls Against Nature. To qualify, we had to perform tasks of personal risk, such as slipping fully clothed under a tipped canoe, searching for the air pocket. Those who succeeded went for trips that lasted up to eight nights. Nancy remembers herself, "a skinny little Jewish girl in the woods, schlepping a canoe and huge parcels. Our parents had absolutely no idea what we were doing." We slept outdoors, survived on meagre rations, ate burnt marshmallows and returned exhausted, with wet bedrolls, colds and insect bites. Here was our opportunity to grow in frightening ways that our sheltered middle-class families would never have permitted, rehearsing our adult roles in deadly earnest.

When the eight-week season ended, we hugged and wept and vowed to return the next year. "I was always shocked to wake up and not see rafters," Joan says, "and that awful sinking feeling that I was all by myself, in my own bedroom in the city, and all the kids were gone."

If Margaret Mead had landed on Kawagama Island in 1955 instead of Samoa in 1925, what conclusions would she have drawn about North American adolescents? Would she have determined that camping was a rigorous and painful preparation for adulthood? A benign rite of passage? A privilege for society's future leaders? She would likely have decided, correctly, that camp was the place where our outrageous individualism was tempered in the fires of peer pressure, where the people we were to become first emerged.

Ruth-Ellen Soles, today a twinkly-eyed troubleshooting press officer for the CBC, lives with her cat, Lydia, in a sparsely furnished art deco apartment on Eglinton Avenue. She swears that 43 years after she last saw Camp Kawagama she could walk through it, eyes closed. "I knew every knot and root and pine cone and twist in the path. I can still see it, feel it, smell it. I could start from our cabin and go all the way over to the basketball court, the Hub, back to Arts and Crafts, then on to Indian Council. I believe to this day I could do it. Absolutely." She has said many times that her days at camp were the happiest of her life. "There was a freedom to just be me. I could participate. I belonged." She thanks Elsie Palter for much of this, because Elsie understood her lack of confidence and did something about it. It was Ruth-Ellen's last year as a camper, her last chance to complete her silver medallion. She had to swim lengths fully clothed and dive off the high tower. Representatives of the Royal Life Saving Society were there to judge for one day. At the end of the ordeal, Ruth-Ellen climbed to the top of the tower and froze. When her time ran out, she climbed down, devastated. Elsie heard about it, and at the last possible moment called Ruth-Ellen into her cabin. "If I can get the people to come back, will you try again?" she asked. Ruth-Ellen said she would.

On one of those windy late-August days, Ruth-Ellen repeated the entire test, swimming against the choppy waves, crying the entire time. Then, on the tower, she said to herself, "I know I'm going to die, but I'm going to dive. There was no way I was not going to do it. Part of it was thinking, Elsie knows I can do this! I've got to do it." Ruth-Ellen did a magnificent dive and never climbed the tower again. "It was like that for a lot of us. She found one little thing that we needed her to encourage us to do."

Early in my career at Kawagama, Elsie did something like that for me. A colossus who bestrode the camp, she was a figure of consummate power. She didn't speak to each camper often, but when she did we paid attention. One night, there was a debate in the Hub: "Is There a God?" Like many kids at that awkward age, I couldn't decide whether I was the village idiot or an undiscovered genius. I sat mute and fidgety, anxious to speak but terrified I'd sound stupid. When it was over, Elsie took me aside. "Why didn't you say something?" she asked. "You're just as smart as they are." A question and a challenge that in later years—for better or worse—encouraged me to speak up at university and as a town planner, a CBC Radio producer and a writer.

We all took a little bit of Elsie home with us. "That woman was a huge force in my life," says Nancy. "Here was a psychologist with all these little specimens to practise on…That little bit of estrangement set just the right tone." Nancy is an elegant matron now, having long ago traded in the almond-shaped eyeglasses for contact lenses. But her personality hasn't changed. "I'm exactly the person today that I was in that cabin." Although trained as a physiotherapist, she admits her life's work has been the cultivation of personal relationships, "being a friend to many people." Hundreds of smiling photographs cover every surface in her busy North York split-level.

A few months after Elsie's funeral, I visited Susan Palter in San Francisco. A psychotherapist who worked for years as an advocate for the homeless in New York, she moved to California with her husband to be near their three children and three grandsons. Susan looks remarkably like her mother, though a softer, more relaxed version. Her summer romance with Charlie Halpern, one of the boys from Buffalo, turned into marriage when she was only 19. Camp is a recurring subject for them. Sometimes Charlie wakes in the middle of the night, says some kid's name—"Wendy Kronish"—and they both giggle and go back to sleep. Seeing us at her mother's funeral was a comfort. "I came down the aisle, and you were all in one row—I'm making myself cry! We'd been through this camp thing together, and it had mattered." When she spoke that day, she looked over at us, "and that ancient connection was there when I needed it."

Susan Morgan feels it, too. Still bouncy and bespectacled, she recently retired from the Toronto District School Board, where she was an administrator, and spends much of her time travelling—as far as Bali and as near as a friend's cottage on what is now officially Kawagama Lake, where she circles our old camp in a motorboat. She says it sometimes startles her when those deep camp feelings erupt. She and fellow Kawagamites have been known to burst spontaneously into camp songs, a reversion that can make non-campers question their sanity. "Other people do look slightly horrified."

It reminds me of a conversation I once had with a neighbour from Baltimore. "In the States," she remarked, "when you meet someone you always ask, What college did you go to? In Canada, it's What camp?!" She found this strange. I found it perfectly normal. Our first taste of freedom, our first flirtation with adulthood, came at camp, not on campus.

When the girls of Cabin 22 became mothers, we didn't have much luck passing on our enthusiasm to our children. We may have oversold the idea. And by then, most camps had changed, become more specialized: kids go now to improve their backhand or their calculus. Rigid rules concerning sex and drugs are hard to police. Many camps have two visitors' days to accommodate fractured families. Nevertheless, 250,000 Ontario kids spent time this summer at 325 sleepover camps. The wealthy still donate so the poor can know, however briefly, the joys and terrors of summer camp.

Camp Kawagama is now Camp Moorelands, founded by an Anglican group that brings inner-city kids up for one-week sessions. But the Cabin 22 girls still think about going back. "People say you can't ever go back, can't revisit time physically," says Nancy, "but I would love to see that space again." Although she can draw every corner in her mind, she wonders whether visiting would animate her memories. As much as she loves her three kids and husband, she'd want to go back alone, or with our cabin. "I try to tell Bernie about camp, and he just doesn't get it." Camp talk is as foreign to him as his conversations about Harbord Collegiate are to her. "That's when you know there are things in your life that are yours alone."

Beth Wolinsky, still a redhead with a nose that crinkles when she smiles, has been going back to camp in her dreams for as long as she can remember. Perhaps because it provided an alternate reality during her turbulent childhood, camp remains a profound influence, the centre of an intensely examined life.

"I think that in my unconscious I've retained that place," she says, "returning there to work things out." In one dream, her grandfather owns the camp and Beth is saying a final goodbye. "As the last boat is leaving, on the last day, my grandfather and I know I'll never see him again. I'm crying, and he gives me a gift, a filigree chest that I've been opening and exploring for years." She thought about going back with two former husbands and her current male partner. "It's as though the camp has become a kind of sanctuary within my psyche, so constant it seemed to be calling me." Finally, she felt the pull so strongly she had to return, literally.

Six years ago, she made the pilgrimage alone from her home in Oakland, California. At Russell Landing, she boarded the boat to camp. (The Trillium, captained by the son of the man who used to ferry us across, still makes regular crossings.) She'd forgotten how long the trip took, the many twists and turns before the island appeared, but there it suddenly was, and she was crying. "I knew exactly where I needed to go and what I wanted to see."

She headed straight to the girls' camp. "When you actually get there, the buildings are rundown, and it's so grown in, so much denser. You couldn't get lost, but it does look and feel different." She pressed through the drizzle to the Hub, then on to Indian Council and down to the beach. She walked to the little amphitheatre behind the baseball diamond, where a birchbark Star of David was once pinned to a tree. She took with her things to leave on the island, and brought back small pieces of rock she now keeps on her desk. She took photographs of beached red canoes, weathered cabins, thick clusters of pine disappearing into mist.

Beth is a disciple of Marion Woodman, the Jungian analyst, and practises art therapy. "The dreams had called me back," she says, "and I needed to express that in some way." After her visit, she made two composite paintings. One combines watercolours with a series of photographs taken on visitors' day in the early '50s. She and her father appear side by side, both dressed in white, with the camp behind them. "It's that whole sense of waiting for the boat, approaching the island, moving closer and closer." In the second painting, Beth stands alone in the water wearing a white off-the-shoulder peasant blouse and saddle shoes. "On this one, I wrote the Hebrew word teshuva, meaning ‘return,' above my name."

Two weeks before Elsie Palter's funeral, a journalist appeared for the first time in Beth's dreams. "I return to camp and find that the owners are an older couple. For years, they ran it as a camp, now more like a farm. I meet a woman who is writing an article about the island when it was a camp. I tell her my experience, how alive it is in me still. She's caught up by what I tell her and decides to record it."

This month, the girls from Cabin 22 will celebrate our 60th birthdays together. Joan Kagan, now a retired high school guidance counsellor, has invited us to her adorable house and pottery studio on a Scarborough street that ends at Lake Ontario, a perfect camplike setting. Ten years ago, when we all turned 50, we came together for lunch at Nancy Shore's. "I got a great deal of pleasure at Nancy's," says Susan Palter, "surrounded by laughter I knew so well." Conversation didn't run deep, but that suited Susan. The older she gets, the more she believes that where memories are involved, non-verbal connections matter more.

Joan can't wait to find out about our lives now. But for this occasion, does it matter? Susan Morgan married a Kawagamite from Windsor, had three boys and a divorce in quick order. Joan married once, briefly, Ruth-Ellen not at all. Two coming to our party have cancer that's in remission. Where to start? Where to stop? Maybe we'll pretend we're back at Kawagama, roast wieners and marshmallows on the beach. I plan to show a video made from a 16-millimetre film Dave Palter shot in 1955. It's impressive: the whole camp recreates crucial scenes from Canadian history with wooden muskets and crepe paper. There are also scenes from our production of Trial by Jury. Together we'll howl over childhood rituals that gave meaning to ordinary events and affirmed the sacredness of our lives and our community. We'll make it 1955 again. We'll tunnel back through time to that island, to that cabin, to the summer that never ends.